Traverse no. 5: David Ellingsen

Welcome to our column that discovers, investigates, and highlights fine art photographic work from an international forum of creatives. Aptly named “Traverse” and written by contributing editor, Michael Kirchoff.

Within this column, I strive to look at photographs and processes that reside outside of the familiar American bubble that we see more often than not. The aim is in examining not simply our similarities and differences, but also the common thread of making photographs in our shared process and goals.

—Michael Kirchoff, Contributing Editor

David Ellingsen

For this installment of Traverse, I wanted to reach back in time and retrieve the work and ideals of a photographer I greatly admire. Having known David Ellingsen’s photographs for several years, this was my chance to investigate the images and the man a bit more, as well as include some thoughts on photography and the subject of conserving our natural environment. Being born and raised in British Columbia, Canada, the surrounding landscape and its denizens are often a part of his everyday life. What I find especially fascinating in making photographs for his body of work, Life: As We’ve Known It, Ellingsen had chosen to use a film that I too have found to be an excellent companion in the creative process – Polaroid positive/negative film. The marriage of these pieces of his visionary puzzle keeps me transfixed on his images. In doing so, this column comes with the addition of a brief interview at the end, to be expanded upon later over at my project Catalyst: Interviews. But for now, let’s take a look at these stunning and thought-provoking photographs and learn about his process.

Photography was simply a passing interest for Ellingsen until his late 20s, when he took a darkroom course at a local college in Vancouver in the late 90s, as well as joining a local darkroom club. With his interest peaked and after the start of the new millennium, Ellingsen completed a one-year, full-time diploma course in Commercial Photography. With this solid technical background, he then took his knowledge and desire and began a career as a freelance assignment photographer for various editorial and corporate clients. After many successful years, he began a three-year transitional period between 2009 and 2012, leaving the assignment world behind with the sole intention of focusing on an art practice.

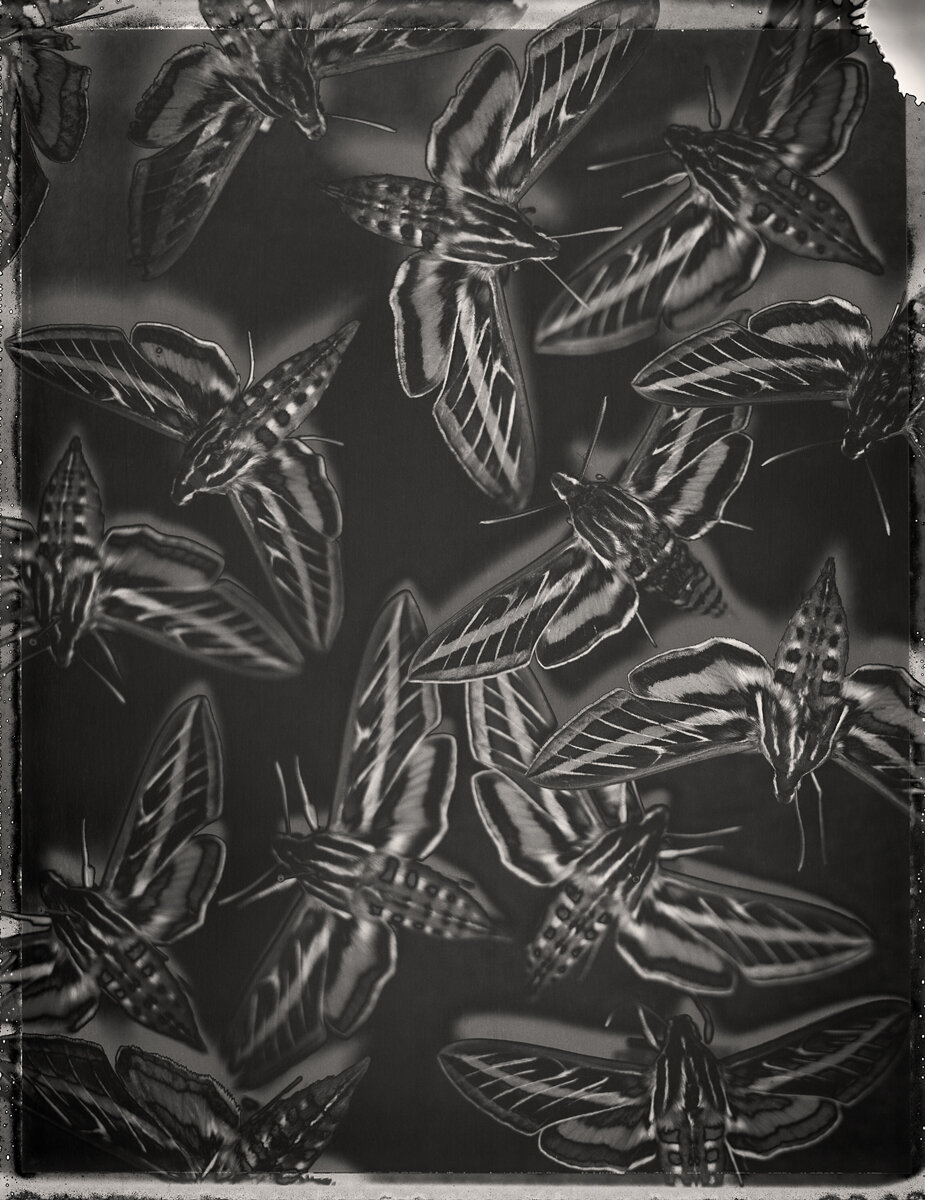

While film was still king at the start of his photographic career, it was clear that there was a transition to digital well underway. For Life: As We’ve Known It, there is a mirroring of the fragility of preservation between the discontinued Polaroid Type 55 film used to make the photographs and the various species of animals seen in this work. Initially attempting to work alone on the project, most of the pictures were created in partnership with Vancouver’s Beaty Biodiversity Museum. According to Ellingsen, “I made many lists of endangered species as a start but was not above taking advantage of the formidable visual impact of some – the albino crow springs immediately to mind – as I was also mindful that over the long term, the majority of earth’s species will be affected in some way by climate breakdown, and not only negatively.” During the process, he had been granted full access to every display, cupboard, and drawer in the museum, to which he respectfully took full advantage. The entire collection incorporates 132 images made over a seven-year span, from 2009 - 2015.

“I would guess like many, it is the alchemy of film photography that I still find alluring.” ~ David Ellingsen

African Grey Parrot, Psittacus Erithacus

With this particular project receiving significant recognition over the past few years, I was also curious about what new projects may be in the works that address some similar topics related to conservation. Ellingsen states, “I am currently working on two major projects. The first is a hybrid of my contemporary photographs with historical and speaks to deforestation. The other uses found imagery exclusively to build collage works, looking to biodiversity. Both are an attempt to use historical imagery to speak of the arc of time since photography began. I heard Carrie Mae Weems say recently; “photography and art tell us who we are,” and with this in mind, now that we have almost 200 years recorded through the medium, I am interested in drawing upon those images to reflect on our civilization’s rather destructive recent past with the hope of informing a better future.”

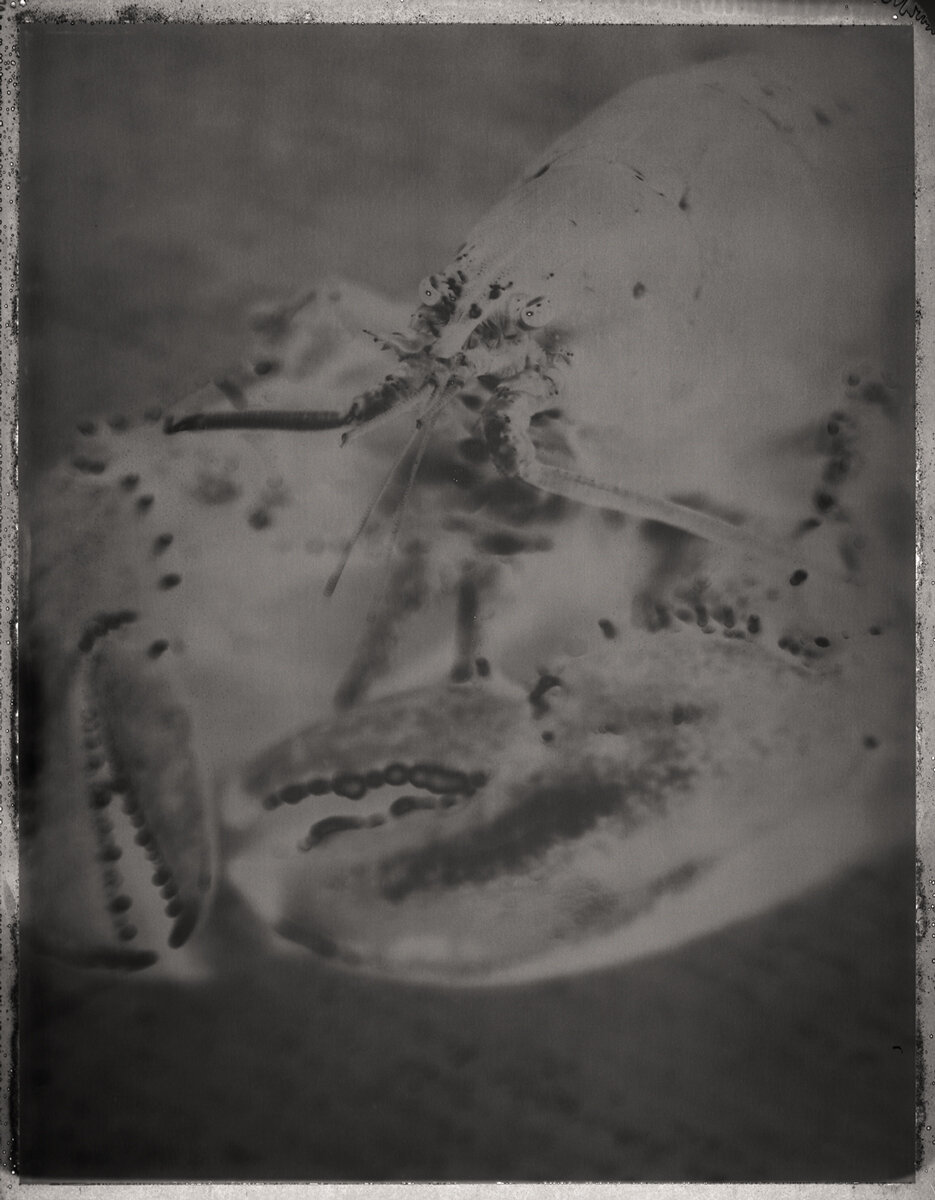

Scalloped Hammerhead Shark, Sphyrnidae lewini

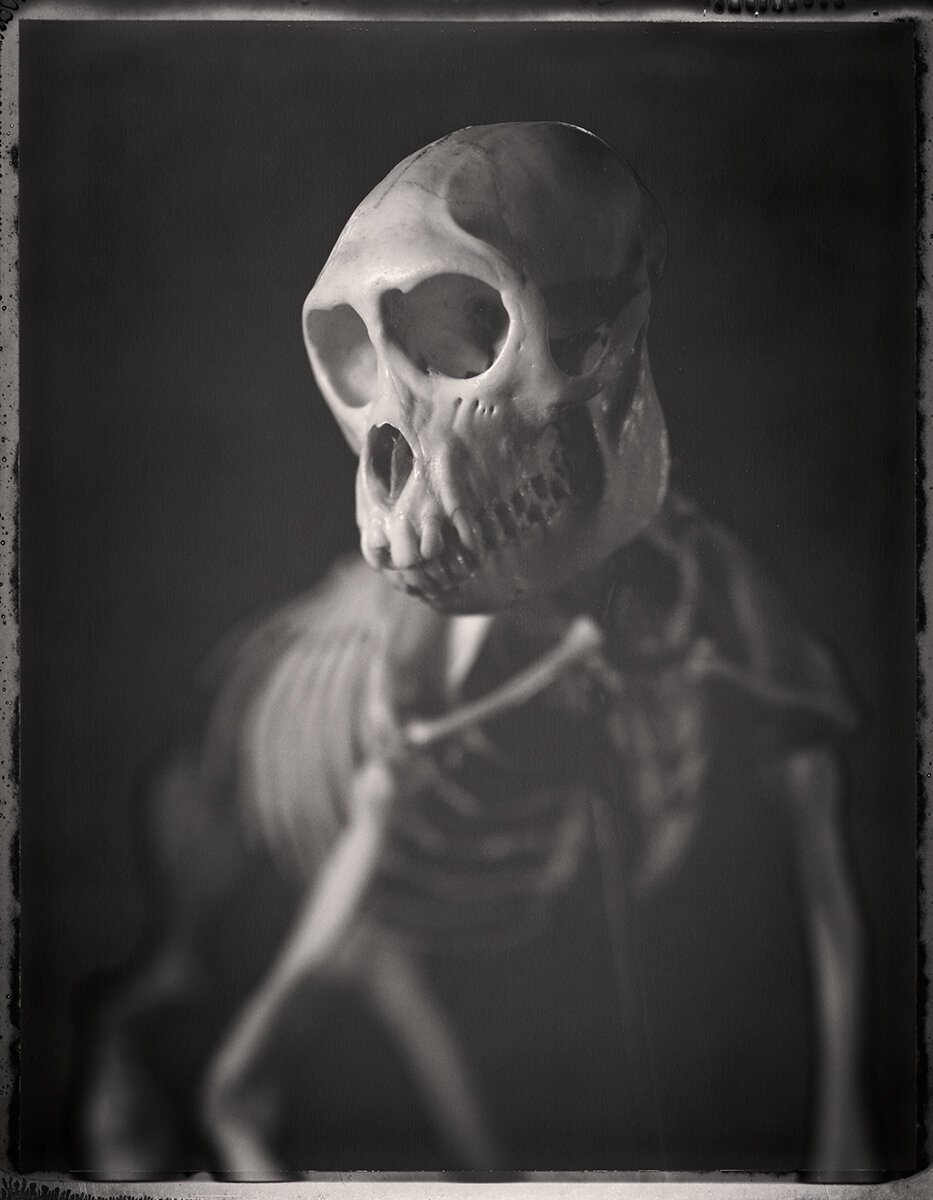

Monkey (species unknown)

In order to punctuate this article with some words of wisdom, I wanted to pose a few questions to David Ellingsen concerning furthering the goals of a photographer with his sights set on the future of our natural environment. I also wish to thank him for his time, patience, and efforts in allowing me to bring his words and photographs to all of you.

Artist Interview

Michael Kirchoff: Thank you for allowing me to ask a few questions related to your photography practice and the ideas behind conservation. As you mention in your bio, this includes topics such as climate, deforestation, and biodiversity. My initial query is what set you off in the direction of including these themes so strongly in your photographic bodies of work?

David Ellingsen: The landscape where I was raised strongly informs my work. I grew up on remote Cortes Island in the Pacific Northwest. My parents had a 96-acre farm, mostly forest, with a large organic orchard and chickens, rabbits, and sheep, on the edge of the sea. The forest and beach were where my brothers and I spent most of our time. I was a sensitive, observant youngster of the cycles of life and rhythms of nature.

The family and community that surrounded me in those formative years were another powerful influence in my life’s trajectory. Like many families with members who work in resource extraction, there is a simultaneous reverence for the wild world and that ran strongly in mine. The wider community of approximately 800 people, many of whom were what you may consider outsiders at the time, also modeled a certain way of being; back-to-the-landers, hippies, activists, draft dodgers, and artists all mixed in with an equal amount of self-reliant, blue-collar folks working generally in natural resource extraction.

Starry Puffer, Arothron stellatus

MK: The work we are featuring here is Life: As We’ve Known It. There is a particular aesthetic associated with these photographs from the film and process you’ve chosen. How did you decide to go this route with these works, again with climate and the natural world being so dominant in this immense body of work?

DE: The 2009 Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico set this series off. Like many, I was haunted by thoughts of the oil pouring relentlessly into the waters and how this would affect the creatures within – and I felt compelled to react. With sea life confirmed as the subject, I then decided upon the Polaroid PN55 film, one I already had much experience with, and one which Polaroid was discontinuing. The soon-to-be-extinct medium seemed to fit the message rather well. The solarization process was another element I was eager to apply in an attempt to underline the magical presence of these other-than-human lives with whom we share this planet.

Bald Eagle, Haliaeetus leucocephalus, No. 2

MK: Have you seen any significant success or attention to your work for the benefit of advancing the knowledge and need to address these topics to and for the public? With such an urgent need to change habits and garner help from those in a place of power, have there been any notable institutions or organizations taking proper notice?

DE: I am fortunate that there have been many; the San José Institute of Contemporary Art, the Royal British Columbia Museum & Archives, the Chinese Museum of Photography, Vancouver’s Beaty Biodiversity Museum, the Datz Museum of Art in South Korea, National Geographic and the Dark Mountain Project, to name but a few. The majority of my resume in fact.

Thankfully, these days it is not hard to find like minds when it comes to addressing the negative impacts of human civilization on the natural world.

About the artist

David Ellingsen is a Canadian photographer creating images that speak to the relationship between humans and the natural world. He focuses on themes of climate, deforestation, and biodiversity loss while drawing upon relationship to place.

Intersections form the foundation of Ellingsen’s practice – intersections of observer and participant, documentary photography and contemporary art, archivist and surrealist. He utilizes a wide range of technical means across the projects, motivated by the evolution of the tools and materials of this restless medium.

Ellingsen’s photographs are exhibited internationally and are part of the permanent collections of the Chinese Museum of Photography, South Korea's Datz Museum of Art and Canada's Beaty Biodiversity Museum and Royal British Columbia Museum. They have been shortlisted for Photolucida's Critical Mass Book Award, appeared with National Geographic, and awarded First Place at the Prix de la Photographie Paris and the International Photography Awards. In his early years Ellingsen was a freelance assignment photographer, eventually working with clients such as the New York Times Magazine, Business Development Bank of Canada, Canadian Medical Association, Oprah Winfrey Network, People magazine, and CBC Radio Canada.

With a practice formed by the landscape he grew up in, Ellingsen lives and works in the Pacific Northwest, moving between his home in Victoria and the island of Cortes, where he was raised, 150 miles to the north. Since arriving as that island’s first immigrant settlers in 1887, his family has continued residence on these traditional, unceded territories of the Klahoose, Tla’amin and Homalco First Nations.

Website: https://www.davidellingsen.com/

About the author

Michael Kirchoff works in the worlds of both commercial and fine art photography. A commercial shooter for over thirty years, it is his fine art work that has set him apart from others, with instant film and toy camera images fueling several bodies of work. His consulting, training, and overall support of his fellow photographic artist continues with assistance in constructing one’s vision, reviewing portfolios, and finding exhibition opportunities, which fill the gaps in time away from active shooting.

Michael is also an independent curator and juror, and advocate for the photographic arts. Currently, he is also Editor-in-Chief at Analog Forever Magazine, and is the Founding Editor for the online photographer interview website, Catalyst: Interviews. Previously, Michael spent over four years as Editor at BLUR magazine.