Keith Taylor interview

Santosh Korthiwada talks with Keith Taylor about his work, hand-crafted processes and the state of photography.

Santosh Korthiwada: How did you take up photography?

Keith Taylor: I grew up surrounded by photographers, both amateur and professional. My father was the main driving force, being a keen still photographer, as were many of his friends. Among them were a few professionals who worked for the national newspapers in Britain, either as photographers or picture editors. In 1966, one of the photographers was covering the World Cup final at Wembley, between England and Germany. A few days later he came by the house and gave me a stack of prints of the England squad. As a six-year-old boy, there was something magical about being given those original 8” x 10” and 16” x 20” glossy prints. But what I remember most was how sharp and detailed they were, because I only ever saw images like these in newspapers or magazines where the reproduction was usually poor. Yet seeing original prints, so large and crisp and tonally perfect was magic. I still have the prints somewhere.

Then twenty-five years ago I married a photographer whose father ran the photography and documentary film department at Honeywell Inc., so I’ve always been surrounded by photography in one form or another.

SK: Which processes are you currently focusing on?

KT: I’m currently working in the platinum-palladium, polymer-photogravure, and gelatin silver processes. I can’t say that any are my least favorite. Each has its merits and I choose the appropriate process to match the image and my vision. They’re all different.

SK: What is your inspiration behind working with polymer-gravure and gum-dichromate processes? Why did you decide to go with these processes?

KT: The gum dichromate process I only ever use for clients, I never use it for my personal work. It’s a beautiful process but I don’t see it fitting in with my images, at least not right now. I had a client who had worked in platinum and gravure and wanted the hand-crafted aspect but in color. Gum dichromate was a natural fit. The process enabled us to easily change the feel and the look of a print by changing the pigments and paper we used.

The traditional copperplate photogravure process was one that I’d been interested in learning since the early 1980s but it involves a lot of time, money and space to do properly. In 1999 I met a printmaker who was working with polymer plates to produce very similar results to the traditional method but with environmentally friendly materials (the plates washout in water rather than acids) and in a fraction of the time.

Each of the processes I work with has very tactile qualities, whether in the paper surface, ink or the metals in the sensitizer. This is what draws me to these processes even though each may display entirely different characteristics. Polymer-gravure allows me to work with a variety of inks and papers to achieve deep blacks and a look that I couldn’t achieve with any of the other processes.

SK: Briefly, can you explain the polymer-gravure process?

The image is output onto a sheet of film as a film positive. The polymer plate is then exposed twice – once with a dot screen and then with the image film positive. The plate is then processed by washing in water for several minutes. The polymer that was struck by light (the highlights) hardens and remains on the plate, whereas areas that blocked the light (the shadows) remain soluble and wash away. This produces a plate with areas that are able to hold ink and others where the ink can be wiped away, just like any intaglio plate.

After drying and hardening the plate, it is handled exactly like any other plate: it’s inked, wiped and run through an etching press with damp paper.

SK: How do you see your process evolving in the next 5 years?

KT: In the past, every year something disappeared or changed – a film, a supplier or a paper etc. Photographers and printers who have been working with historical and alternative processes are used to this; it’s not new. The British photographer Frederick H. Evans famously gave up photography when his favorite paper became unavailable and the alternatives were too expensive, and he was unwilling to adopt alternative methods. Today, photographers are used to changes and products being discontinued, yet these alternative processes are more popular than ever and manufacturers are beginning to see this and are willing to manufacture papers and materials specifically formulated for these processes. So the future looks good.

SK: Why did you decide to get into specialty printing?

KT: At the time I was working for a company and I became disillusioned with producing the same-looking 8” x 10” prints all the time. At that time, in London in the early 1980s, there were probably 3 or 4 printers who specifically printed for exhibitions and portfolios. I printed images from the heart and in a way that I would like to see them. It was a steep curve as photographers didn’t really know what could be achieved in the printing other than a straight black and white print. I started reading old books of formulas and experimenting with toning. Virtually all of my prints were toned in some way, even though that may have been just a subtle selenium toning for permanence. Now, much of my work for clients is divided evenly between platinum, polymer gravure, and silver.

SK: What do you think is the future of alternative processes in the field of photography?

KT: The term ‘alternative’ is misleading. It originated in the 1980s when silver printing was the standard and these processes were the alternatives. Now that inkjet printing is the standard I think of these as more ‘historical’ processes than alternatives.

The future is bright for anyone working with any of these processes and with the ability to create the large negatives that they require using inkjet printers, they’ve become even more accessible to photographers. You don’t even need a true darkroom for most of them. It’s a liberating time to be working in photography.

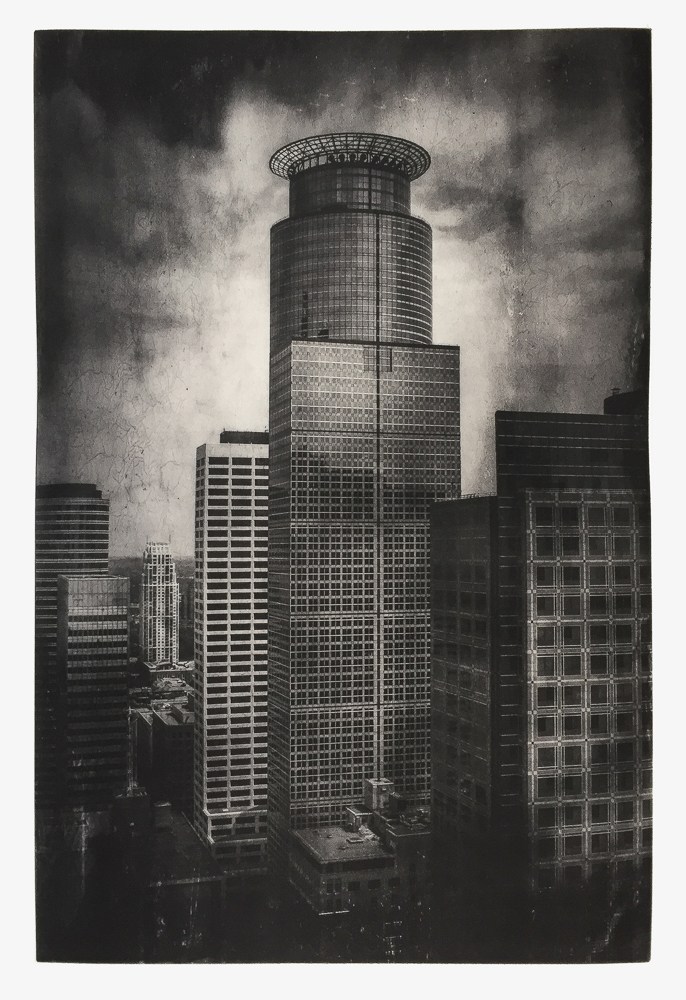

Keith Taylor is a London-born artist who now lives in Minneapolis. Taylor uses photography to render landscapes, both real and imagined, playing with tensions between geography and experience. He is particularly interested in applying experimental technology to push the capabilities of handmade historical photographic printmaking processes.

Taylor's has been widely exhibited across the US and UK, he is a three-time recipient of fellowships from the Minnesota State Arts Board, and was awarded a place in the Minnesota Center for Book Arts/Jerome Foundation mentorship program. Taylor teaches workshops at the Highpoint Center for Printmaking and the Minneapolis College of Art and Design.