Poignant Pics no. 49 - On Alayna Pernell's “With Care To Ms. Maudelle Bass Weston”

Welcome to no. 49 in our series Poignant Pics where our editor, Diana Nicholette Jeon, writes about Alayna Pernell's “With Care To Ms. Maudelle Bass Weston.”

Making the Invisible Visible

“It seems to me that obliviousness about white advantage, like obliviousness about male advantage, is kept strongly inculturated in the United States so as to maintain the myth of meritocracy, the myth that democratic choice is equally available to all. Keeping most people unaware that freedom of confident action is there for just a small number of people props up those in power and serves to keep power in the hands of the same groups that have most of it already.”

How do I, a white woman, talk about a work rooted in the history of American slave ownership and its aftermath? I feel unqualified to comment effectively.

As a woman, I have thought twice about where I go and when. Yet rarely have I had to think about my skin color as a factor in such outings. I haven't had to fear being arrested or, worse, killed because of my skin color. My family may have come from poor Greek peasant stock, but they were not owned by anyone, at least not during the last couple of centuries, which is as far back as I know.

I live in Hawai'i, a place encapsulated by a complex history. One where white western men's dreams of manifest destiny and their supremacy assumptions intertwined with the work of missionary do-gooders come to save the 'heathen' Natives from 'damnation.' Ultimately, this resulted in the overthrow of the Queen Liliu'okulani and the Sovereign Nation of Hawai'i. My skin color is the same as those responsible for it happening. The same as the current ruling class, even though whites are not the majority population here. Within this place, I am a white woman married to a brown man, so I have entree to circles I might not enter otherwise—more privilege of a sort. I am also the mother of a mixed-race son, born and raised in Hawai'i (until he was four years old when we moved to Baltimore for three years.)

My husband was born and raised in Hawai'i, and until 2003, by choice, he never lived anywhere else. He was born just short of a year after Hawai'i achieved statehood. Don't even get me started on that. It took many years before the US governing bodies considered a place made up of people of color to be worthy of statehood, even though they appreciated the money they made here on the plantations that bore the names of the original missionaries. I attended a graduate program in Baltimore, MD, and we all relocated, for me. None of us remember that time fondly, although our reasons for that are each very different. In my husband's case, he experienced a lot of racial prejudice and assumptions about "where he was from." We would be driving down the I-95, and some redneck would yell, "Go back to the country you came from!!!" followed by some expletive name-calling. My husband has a temper and would engage back. I lived in fear of all of us dying if one of these people pulled out a gun as a response. That thought was always present, but it was nowhere near as prevalent as it would be if I had to fear that engaging in everyday life activities, like jogging, or driving, might put me in handcuffs—or much worse. I can empathize with what my husband endured there or what my son says he experienced during the semester he went to the mainland for college. But it will never be my experience, as I am privileged by my skin color to avoid it.

So I return to my opening question. How do I talk about work that will always be apart from what I have or will experience(d)? Although some people, like curator Maurice Berger, were successful at it, I feel I may fail to do justice to this touching work by Alayna Pernell.

With Care To Ms. Maudelle Bass Weston

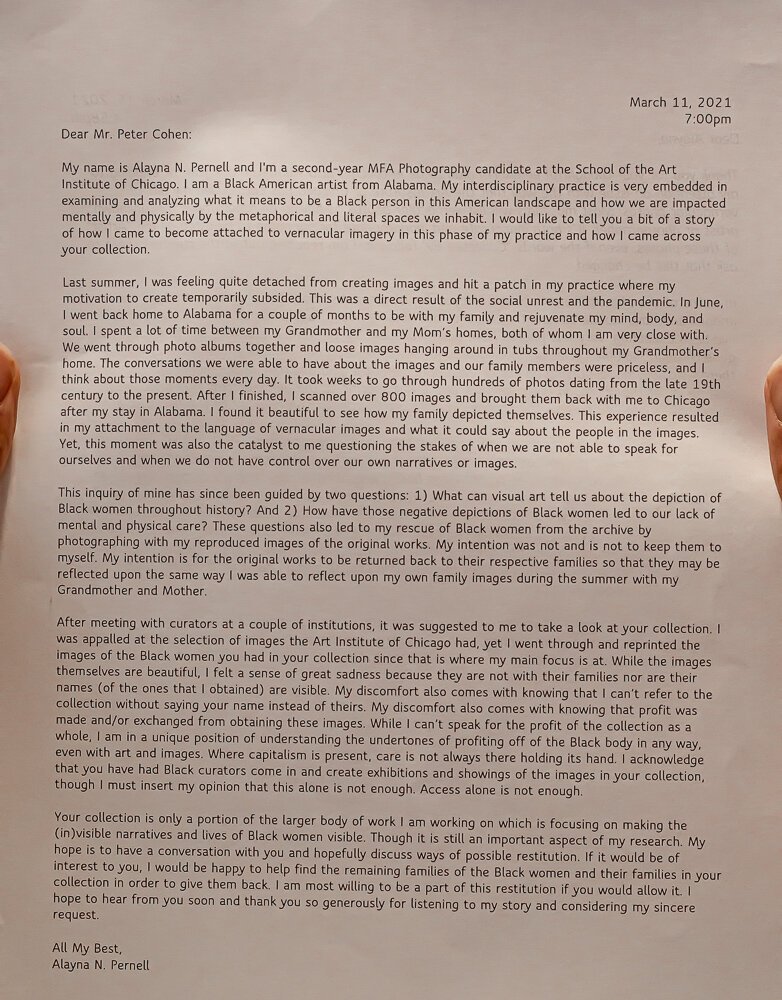

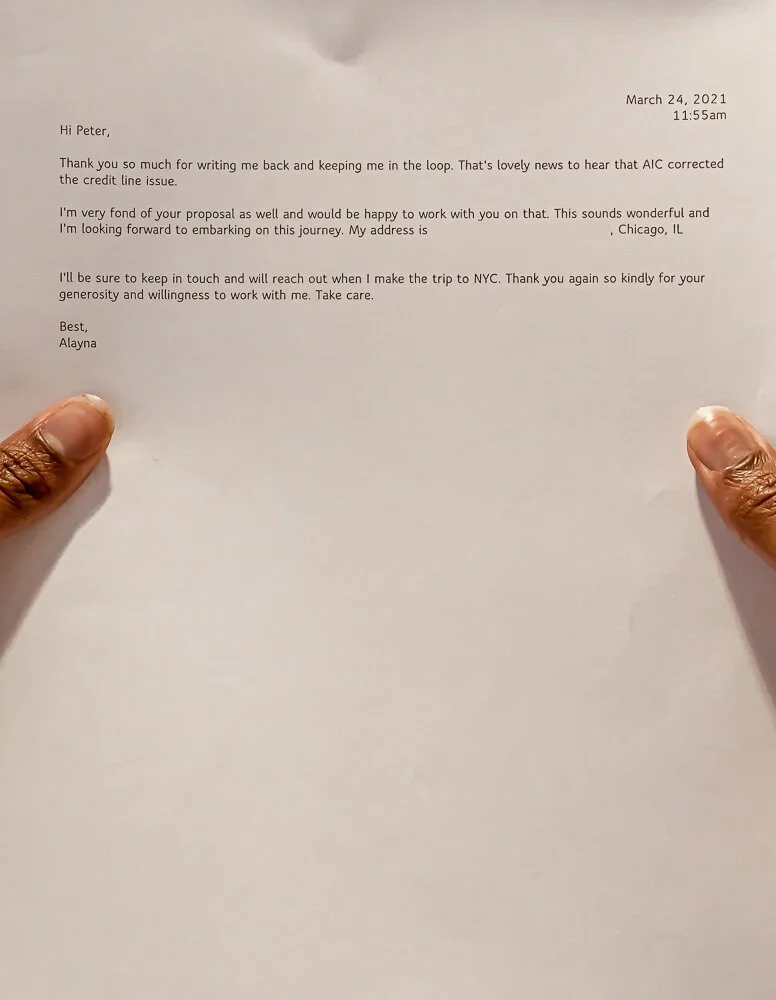

I found Alayna Pernell's series while perusing the story section on PH Museum, and the cover image, the one I have shown here, riveted me. Once I arranged to feature this image, I sought to learn more about Alayna's project. To this end, I have included two additional photos from her series. These are photographs of her correspondence with Peter Cohen of the Art Institute of Chicago. In my opinion, they further our understanding of her work by showing her thought process in bringing this project to fruition.

As a mother, I was immediately swept into the story via Pernell's use of her hands. Protective, covering the seemingly naked figure, caring for her. Additionally, there is a sense of history generated not just by the style of the image of Maudelle Bass Weston but by the quality of the re-photographed image. This is due to Pernell's hands having more detail and greater clarity. Maudelle's gaze also impacted me. Staring off into the proverbial distance, seemingly lost within it. Purposely–as a way to separate herself from what she was experiencing. It also seems that Maudelle may wish the bushes covered more of her because her stance is as if she was trying to back into them.

About this series, Pernell states,

"I have spent the past year researching and uncovering suppressed images of Black women held in photographic collections at the Art Institute of Chicago. The images I have found and researched thus far depict the exploitation and violence towards Black women. I excavated, re-photographed, re-captioned, and re-contextualized the original works. By engaging with these images with the intervention of my hands and my body, I rescue and protect Black women's bodies and their humanity so that they can be seen and heard. With my ongoing body of work entitled Our Mothers' Gardens, I beg for more than the visibility of Black women in institutional collections and restorative justice. I also desire for the issue around institutions holding and silencing collections of visible and (in)visible violent visual depictions of Black women to be further highlighted."

One other thing I found on her website that I consider necessary is this artists statement:

"My interdisciplinary practice considers the gravity of the mental wellbeing of Black people in relation to the physical and metaphorical spaces they inhabit. Visually, I attempt to create space for healthy dialogue to occur. I hold firm to the idea that in order to promote understanding, love, and empathy between each other, it is vital to have difficult conversations."

I hope that I did not misportray or misread the message that Pernell wants all of us to hear. I also aspire that my featuring this image may cause some worthy conversations to happen, difficult or not. I also yearn that this work enters your psyche and stays there, as it did for me.

I urge you to visit her website to peruse her project as it is meant to be seen, in its entirety. I will be watching to see what Pernell does next because I feel her work is essential. Given how American society seems to be sliding backward rather than marching forward in supporting civil rights, it is more than important. It's necessary. Bravo, Alayna!

Artist Bio

Alayna N. Pernell (b. 1996) was born and raised in Heflin, Alabama. In May 2019, she graduated from The University of Alabama where she received her Bachelor of Arts in Studio Art with a concentration in Photography and a minor in African American Studies. She received her MFA in Photography from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in May 2021. Pernell’s practice considers the gravity of the mental wellbeing of Black people concerning the physical and metaphorical spaces they inhabit. Her work has been exhibited in various cities across the United States.

Pernell was named the 2020-2021 recipient of the James Weinstein Memorial Award by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago Department of Photography and the 2021 Snider Prize recipient by the Museum of Contemporary Photography.

She is currently the Associate Lecture of Photography and Imaging at the University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee.

More of her work in this series and beyond can be seen at https://www.alaynanpernell.com

Author Bio

Diana Nicholette Jeon is an award-winning artist based in Honolulu, HI, who works primarily with lens-based media. Her work has been seen both internationally and nationally in solo and group exhibitions. Jeon holds an MFA from UMBC.